You are here: Home1 / Challenge Domains2 / Sustainability Transformations in Africa3 / The hidden violence of conservation and the case for socio-ecological ...

The hidden violence of conservation and the case for socio-ecological reparations

PRETORIA – Conservation is widely regarded as a moral good, a safeguard for nature and future generations. Yet it is also a site of violence. This violence is often invisible, deeply embedded in and shaped by a colonial logic that continues to violate communities.

That was the central argument raised during a panel discussion at a side event on socio-ecological reparations held during Africa Week 2025 at Future Africa, the University of Pretoria’s (UP) pan-African platform for collaborative research.

The session, titled ‘Socio-ecological Debt to Africa: Options for Reparations’, was moderated by Professor Maano Ramutsindela, Future Africa Research Chair in Sustainability Transformations. Panellists argued that justice must account for both the environmental and human costs of Africa’s conservation history.

Colonialism’s enduring footprint on people and land

Providing the historical context, Professor Adekeye Adebajo, a Research Fellow at UP’s Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship, described slavery as Europe’s “original sin” against Africa. He explained why examining and talking about reparations is necessary in today’s political climate. “This seems to be an inauspicious time to actually be fighting for reparations because we have in the US a white supremacist Christian regime that is basically launching one of the fiercest assaults on diversity.”

“It’s even threatening to cut off funding from the Museum of African American History and it’s wanting in some ways to erase history… And so, this is actually the most important time to put forward with the requisite academic rigour the accurate version of history, both slavery and colonialism, and make the case for reparations.”

Drawing on his recently launched book, The Black Atlantic’s Triple Burden: Slavery, Colonialism, and Reparations, Prof Adebajo outlined how Europe’s industrial development was funded and fuelled by centuries of extractive practices in Africa which led to environmental degradation and the displacement of communities. He made the case for a broader understanding of reparations that includes debt annulment, institutional reform and the return of looted artefacts, among other forms of redress.

Degradation of Africans through conservation

Frank Matose, Associate Professor in the University of Cape Town’s Department of Sociology, and Dr Tafadzwa Mushonga, a Research Fellow at UP’s Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship, put the spotlight on the ongoing violence embedded in Africa’s conservation regimes. Drawing from their research and co-authored book, The Violence of Conservation in Africa, they argued that dispossession continues under the guise of environmental protection.

“What are African people thought of as? Essentially, non-human. And it carries on today in the pursuit of environmentalisms,” said Professor Matose. He and Dr Mushonga described how national parks, game reserves and other protected areas have often been created by removing people from their ancestral lands, erasing their cultural ties to nature and criminalising traditional practices.

“I’m going to speak about violence against people in the context of biodiversity conservation or protected areas management in Africa,” Dr Mushonga explained. “This is the violence experienced by people living next to or in our national parks, game reserves, forest reserves, big and small state parks.

“Every time I say that I want to speak about conservation and violence, there’s always this reaction from people that: ‘How can you speak about violence in conservation?’ That’s exactly what it is. And I’m not surprised [by people’s reactions], because when you go to Kodo National Park [in Japan], Masai Mara [National Reserve in Kenya], or whichever national park you go, you’re not going to see this violence. You’re not going to see it written on the wall. You’re not going to see it even written on the gate that, ‘Now you’re entering a violent space.’

“The combination of violence and conservation almost sounds like a contradiction, because conservation is known by many as the means for protecting nature and its beauty. But the reason why we often do not see the violence of conservation is because it’s so embedded, it’s structural, and it’s so established to a point that certain forms of violence, or even practices of violence, have become acceptable and have been normalised as processes that date back to colonisation.”

This framing led to a broader conversation about socio-ecological debt, particularly in the context of conservation. Dr Mushonga emphasised that communities are not only physically displaced by conservation policies, but also rendered invisible or criminalised.

She noted that locals are often labelled as poachers for continuing traditional subsistence practices, and park rangers experience psychological trauma from shoot-to-kill mandates, where even innocent community members are treated as poachers. The communities who are the most affected by this violence are those least likely to benefit from tourism or ecological programmes, Dr Mushonga added.

Legal tools are not enough

Dr Justice Mavedzenge, Senior Legal Advisor and Programmes Director of the Africa Judges and Jurists Forum, provided an overview of how international legal frameworks can and cannot serve Africa’s pursuit of reparative justice. While legal tools such as the United Nations Basic Principles on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation offer some guidance, he argued that law cannot lead the way.

Dr Mavedzenge explained that the fundamental limitation in international law when it comes to African reparations claims is that no judicial body currently has the authority to issue binding legal decisions on such matters. He said while the International Court of Justice (ICJ) could have served as a suitable forum, it can only adjudicate cases if all involved states agree to its jurisdiction.

He noted that while advisory opinions from ICJ may lack binding force, they can be used strategically to keep reparations on the global agenda and pressure states to act. He also warned that many former colonial powers have deliberately limited the jurisdiction of international courts to avoid accountability for historical injustices.

“My view is that the fight for reparative justice is fundamentally a political question that will be resolved through political action which, however, needs to be reinforced through legal tools. It’s not the other way around. Why? Because we still haven’t decolonised the law. So, we can’t make law the primary tool for the struggle. The law was not even the primary tool for the struggle in the early years of decolonisation. The primary tool was political action, and then the law reinforced political action.”

Future Africa is building on these conversations to assess and offer options for reparation for human and environmental harms.

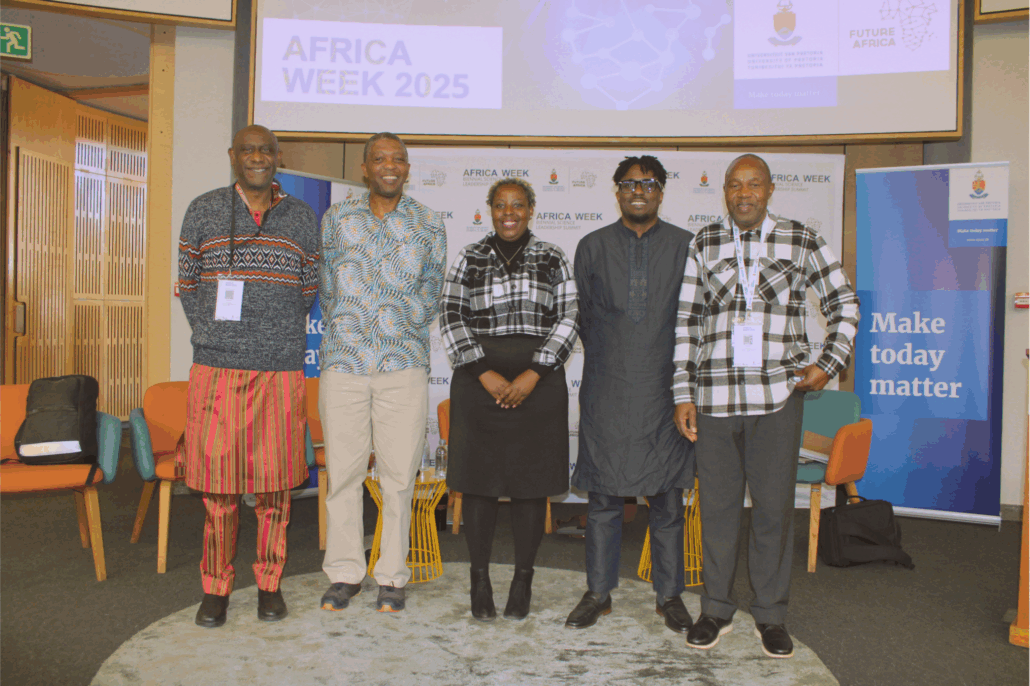

From left to right: Prof Adekeye Adebajo, Prof Frank Matose, Dr Tafadzwa Mushonga, Dr Justice Mavedzenge and Prof Maano Ramutsindela